what is reclaiming anyway?

in an era of "reclaiming The Classics TM", is it erasure and whitewashing we seek instead? (some general strawmanny thoughts)

Babes, we are in an epidemic of Greek myth retellings. I’m tempted to blame Madeline Miller save for the fact that I do enjoy her writing, but it feels like everywhere I look there’s a new take on an old myth. And they all, without fail, market themselves as feminist retellings that seek to Reclaim Greek Mythology. Like fuck those old misogynists, what do they know!

But the thing I keep bumping up against, and the reason I so rarely pick them up is that they so rarely seem, well, feminist.

Listen, I am not the boss of all feminism, and I don’t pretend to have the best knowledge of ancient Greek (or Roman!) society—I have an interest I’d like to deepen, I like the syncretic societies of the ancient Mediterranean (Babylon, someday I will learn more about you), I listen to Natalie Haynes’s BBC 4 podcast, I watch Mary Beard documentaries and spend a lot of time thinking about Clytemnestra, Medea, and Caligula, though I retain very scant information about any. Those are my limited credentials.

What I do have is a desire for liberation from patriarchy and a belief that feminism is not a thing you are, it is a thing you do, and a framework for analysis rather than a checklist. I also like, think women are really cool and that we’re better as full and complete and imperfect human beings. I like a gremlin of a girl, a she-devil, a viper, a vixen, and prefer Bella Wilfer to Lizzie Hexam, someone thorny and unlikeable, but empathetically so, who expresses a full range of humanity and emotion.

So that is where I am coming from when I say that what I have noticed is a tendency towards sanitization, and the smoothing out of the unpalatable aspects of a Bronze Age society that I just don’t think fully engages with what it means to be a woman in that kind of world, or the kinds of people that it might produce.

The past, they say, is a foreign country. Its mores are not our own. Its gods are not gods that we can understand, the kind of hands-off laissez-faire gods who are anti-interventionist and only judge us once our capacity for harm is neutralized through our unbecoming. Its gods are real and capricious, who can materially harm or help them through a freak storm or some vapors from stone. Perhaps it’s true that women in the hands of Aeschylus run on a spectrum of weak and servile to harpylike shrew, with a natural tendency towards badness and evil, morality tales about the risks of Letting Your Woman Run All Over You TM.

I understand the impulse to buck against this. I am hardly sympathetic to men portraying a woman running around falsely crying rape because she is just So Overwhelmed By Her Lusts for Her Ugly Old Husband’s Hot Young Son (sorry, Phaedra).1

But what does it mean here, the act of reclaiming? To assert agency where there is none (Persephone’s abduction by Hades, thanks, Tumblr), or to take agency away where it does exist (the sorceress Medea choosing to kill her children in an act of vengeance against Jason) in order to make these difficult women and their difficult stories more palatable for our consumption. What kinds of stories are we telling ourselves about the past, this other country? Do we attend to their truths, their realities, what it means to be a woman in the specific time and place they would have been women? Or are we ignoring who they are and the lives they lived in order to claim them for some kind of ahistorical Universal Womanhood that does not see a difference between their material conditions and our own, even though the expressions of our patriarchies differ? Or to rephrase—am I taking back a tradition that belongs to me or am I laying claim to something that is not mine at all?

I struggle with this dual-action girlbossification—on one hand trimming back the societal unruliness of villainous Greek women that comes from their violent, disruptive claims to agency, on the other asserting that the heroic ones had broader societal agency than what they were typically allowed to access2. There is a lot here that I think comes from good impulses—the knowledge that so much of what we know about women comes not from their own words but filtered through men and patriarchy, and I doubt the account of, say, the Rape of the Sabine Women would be framed in quite the same way had women been the ones to tell it—but that is the point, isn’t it? That anecdote would not have occurred had women been in a position to tell it in the way they chose. Women have not had an equal voice in history or a say in how we’ve been represented by it because we have lived in societies that did not afford us the room to speak up, or learn to write on as wide a scale in order to leave our voices behind. The stories that trickle down to us are the way they are because they have been produced by the societies that have been structured in a way so as to produce them.

Perhaps this sounds like circular logic. Maybe I should put it this way. Would Persephone have been abducted by her uncle-husband and tricked into eating the pomegranate seeds that bound her forever to the Underworld and changed her irreconcilably3 in a society where the abduction of young women was taboo, and suitably punished? Or could it have only happened in a society that already deemed young girls marriageable subjects and as objects of barter between her father and his associates that the myth of the goddess of spring unfolds the way it does? (Attend Zeus’s role in the Persephone story.) What kinds of social realities do the Hades/Persephone retellings that romanticise her abduction and villify the mother who is trying to do nothing more than get her daughter back bely? And is that truthful, or is it wish fulfillment for a prettier, more easy past, one that doesn’t force us to think about taxing things like marital rape and abduction?

I also wonder if these stories of vengeful women can be understood as power fantasies—how many women, without the power to change their own circumstances, fantasised about being a sorceress like Medea, who had the capacity to kill their husbands’ lovers and take the thing he values most away from him. There is something so deeply frightening in that act, a mother killing her own child, that shocks and transgresses. That she does it in anger, in vengeance, like some kind of protean goddess—sure it might be a warning for men, but I can’t imagine it wouldn’t have made some of the women feel seen (not that they would have gotten to watch Medea at the theatron, being, well, women).4

I’m not saying we have to stop; I’m not saying we have to do anything about it at all—I’m certainly not above lapping up every Death/consort story that comes my way. The Hades/Persephone dynamic in Hadestown is genuinely one of my favourite things. But I do think we need to take care in how to position these reads, and to avoid the pitfalls of marketing something as more comparatively feminist than their source material simply because they have been updated to appeal to modern sensibilities, because what we’ve done is turn these women who were considered unruly in their own age into women that suit the sensibilities of ours. There is a taming there that does not strike me as being particularly subversive or challenging, which I do think feminist literature should be. Men like Heracles and Theseus (fuck Theseus), and Jason, get to exist in the common without having their evils and selfishnesses sanded away to justify their right of place. Is it just that women must?

The kind of feminist lens through which I would love to revisit these stories are not ones that are uncomfortable with how unpalatable women can be, as individual human lives, but that rather sits in the discomfort, provokes us to wrest with it, asks questions of us, challenges us. I love women like Clytemnestra and Medea precisely because they are wild. There is a rage in them—untamable, frightening perhaps to a society that compels women to be meek and pliable. They are necessarily taboo figures because they do not comply with the womanhood that has been handed to them. Clytemnestra is a twice-married princess who takes over as regent of Mycenae because her husband is away at war and her children are too young. She cheats. She lies. She blasphemes. She murders. She is open in her exercise of political power and intellectual might. What does it mean to love her? What kind of society would forge her, only to cage and punish her? What does it mean, for example, if she is a good mother to Iphigenia at the expense of her eventual murderers, her other children, Elektra and Orestes? Why must father-killing be avenged with mother-killing? If we take it on its face—that fathers are more valuable than mothers—what does that then tell us about the role of women in the Athenian society that produced the Oresteia, how “woman” as a category is created and reinforced? What does it mean that she kills poor Cassandra, trafficked war bride who was entirely innocent and undeserving of her fate? What does it mean that she was a slaveholder? What does it mean if she wrought some of her own suffering, instead of being brought to it by victimhood?

Here is the thing, right, the past does not belong to me. It was not taken from me, it was taken from them, those women, in that time, in that region. (No small coincidence that many retellings don’t particularly attend to the historical and modern diversity of the Mediterranean, preferring to set it in what author Maya Deane terms a “nowhere land”, as the former would require a recognition that these women are 1) different from us and 2) have a context. Andromeda is from Ethiopia, for god’s sake; these are real places that have always had real people and real cultures that have been passed down to other real people in the modern day.)

I don’t seek to reclaim because I’d rather understand, to be curious about these women, as they may have existed or as they reflected, distorted, gave voice to or silenced women who did. I want to honor women as they were, attending to the fact that they were a subject population with limited power, some of whom, like Aspasia, found ways of subverting their society and finding ways to accumulate personal power5, others of whom—the majority—who made do with the hand they were dealt. If there are only bad options, why should we balk from women who make an even worse choice because it gives them agency? Why wouldn’t a woman become a villain? Does every woman always have to justify everything we do? Is it empowering to make us inherently angelic creatures motivated by victimization—while also asserting that power comes from that victimhood rather than any ambition, any desire, any moral-social upending? What if when women wield power, it is not any less thorny or perilous as when men do it?

Why must they be cut down to size and made consumable?

Whatever, all of this is very low stakes nerd complaining, mostly about myth rather than about reality, in essentialist broad strokes instead of in specifics, but stay tuned for my next rant about how how this phenomenon also maps onto real women like Marie Antoinette (incompetent), Mary Queen of Scots (incompetent), the Romanovas (incompetent) and Wu Zetian (not incompetent, but god, at what cost?). TL;DR, girlbossing up history rips the humanity and dimension out of individual women by continuing the patriarchal assertion of a singular mould of acceptable womanhood, and I don’t like that just because it replaces a historical model with a modern one! It’s dishonest and flattening either way! Maggie Beaufort, you will have your day. Marie, someday you will have a book/movie/show/anything that attends to the layered truth of your character instead of doing things like making absolutely absurd claims to your nonexistent feminism to make you more likable, as though you could not be fascinating and nuanced and interesting to read about without also being liked. (The women who marched on Versailles might have some thoughts about that? Possibly.)6

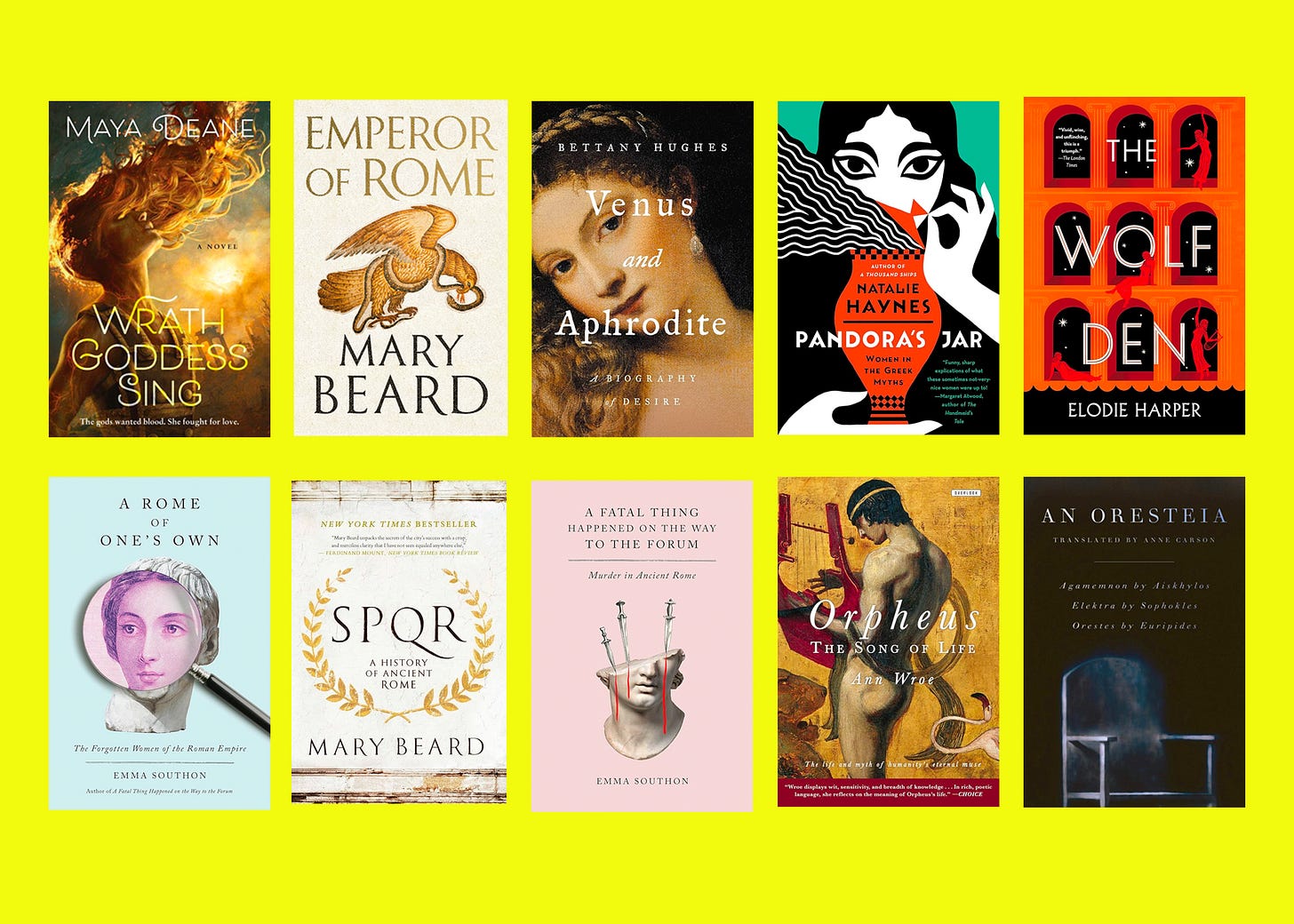

Anyway, here are some Greco-Roman myth retellings + nonfiction + historical fiction + translations I do quite enjoy, lest I only be known for griping:

Women are great! Can we afford them more complexity, the room to be wrathful and ungovernable, the ability to actually challenge the status quo and discomfort rather than slotting neatly into whichever mould best suits comfortable social norms? IDK!

Though, frankly, I think Phaedra is more interesting even taken at face value as a false crier of rape than she is given credit for, particularly a) as a wife of Theseus who is also a sister of Ariadne and b) as a plaything of Aphrodite, since people tend to forget the latter’s involvement in this story or the very real belief in the very real hand that gods play in these myths. This entire episode is complicated by—and falls apart without—the presence of Aphrodite, Artemis, and Poseidon, whose powers, it’s worth emphasizing are literal and real to the people from whom this story originates.

Nor is it as simple as a story of a false rape—it is a tragedy, and Phaedra is a victim of that tragedy, as incited by Aphrodite as punishment for Hippolytus’s impiety and his overzealous dedication to Artemis. He’s not Phaedra’s victim, he is Aphrodite’s, and it’s Aphrodite who takes Phaedra’s agency away from her; I don’t know if we can or should take these stories literally, or as capable of standing alone without the presence of the gods or a belief in their power.

(Sidenote, but I do find it fascinating that the two most consistently misogynist gods in these myths are Aphrodite and Athena. There’s something chewy there, I just haven’t given it enough thought yet.)

Though it is of course the case that in all times women have found ways to assert ourselves regardless of the limits imposed upon us, and there often was more sexual freedom in particular than we imagine when we think of The Past; what I am saying here is that the baseline attitude towards that freedom does not seem to be informed by their own societies but rather more by our modernity and the attitudes derived therefrom. Anne Hathaway did marry William Shakespeare already pregnant, and eight years older than he, but their social relations still would have been informed by Tudor moral & legal frameworks, for example.

Which, my god, how do you not read that as a way to reckon with sexual assault? A young girl taken by an older man with intimate access to her through his relationship to both her mother and father, tricked into an act whose consequences she cannot foresee, is changed forever by it and is bound to him for the rest of her life? Especially when marriage to one’s rapist was a norm well into the 20th century—and sometimes into the 21st as well. I rarely get actually viscerally angry about the kinds of novels I’ve described in very broad strokes here, but this may be the exception. Most are well meaning attempts to Feminist TM up stories from an intensely patriarchal age, this just reads to me like rape apologia.

Alternatively Medea could be a great vehicle for an exploration of postpartum psychosis.

Though I again hesitate to call that impulse feminist, just that a feminist reading on Aspasia would differ from a patriarchal one; I don’t actually think accumulation of wealth and power are good no matter the gender of the accumulator, IDK

I also have some secondary thoughts about the way this phenomenon maps on the The Classics TM as in the literary canon and the ways in which trying to force historical texts into our modern mores instead of meeting them as they are actually leads us to think & learn less about how racism, sexism, homophobia, etc. are constructed, defined, and reinforced, but has this not been long, and discursive, and repetitive enough? (I immediately started the next sentence with the beginnings of a rant about what Charlotte Brontë’s racism vis-a-vis Wuthering Heights can teach us about racism in Victorian England and why problematic is the start of a conversation and not the end of one, and then had to force myself to delete it.)